This article was originally published on Neocha and is republished with permission.

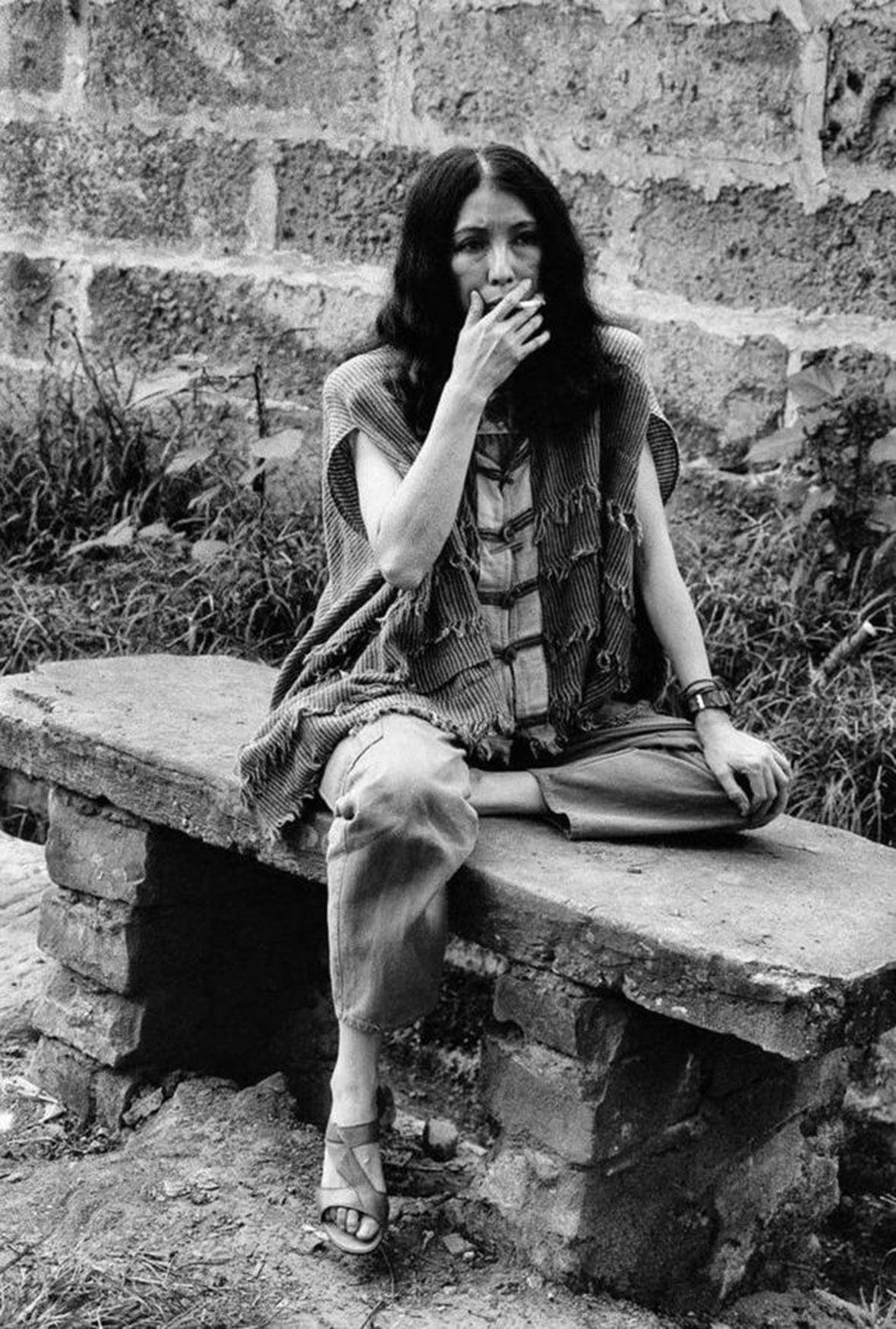

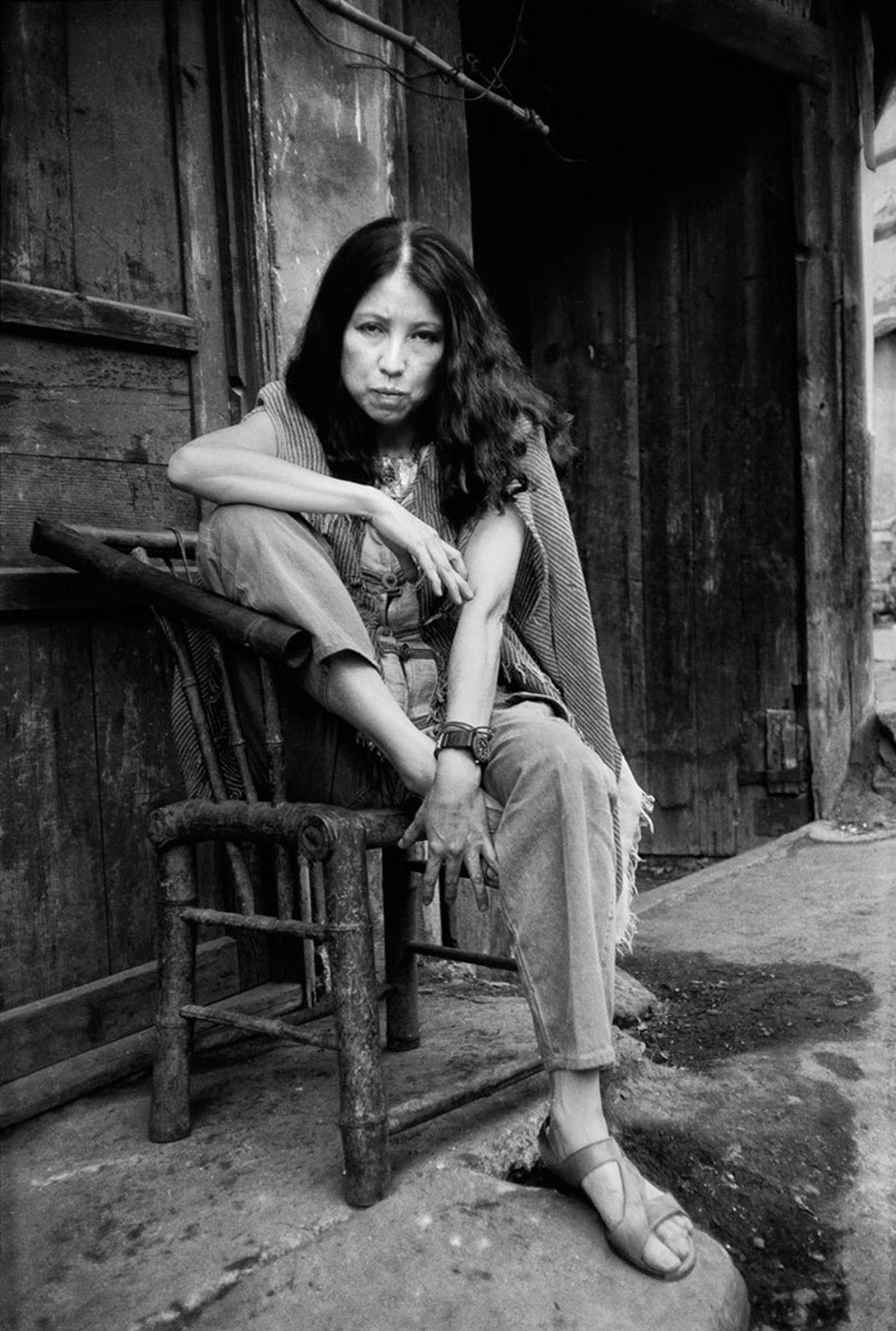

For some people, the desert holds a special allure. They’re drawn to its severe beauty, its terrifying openness, its punishing sun and frigid nights. For readers of Chinese, perhaps the most memorable figure to dream of the desert—and one of the most singular travelers of the 20th century—is the Taiwanese writer known as Sānmáo 三毛.

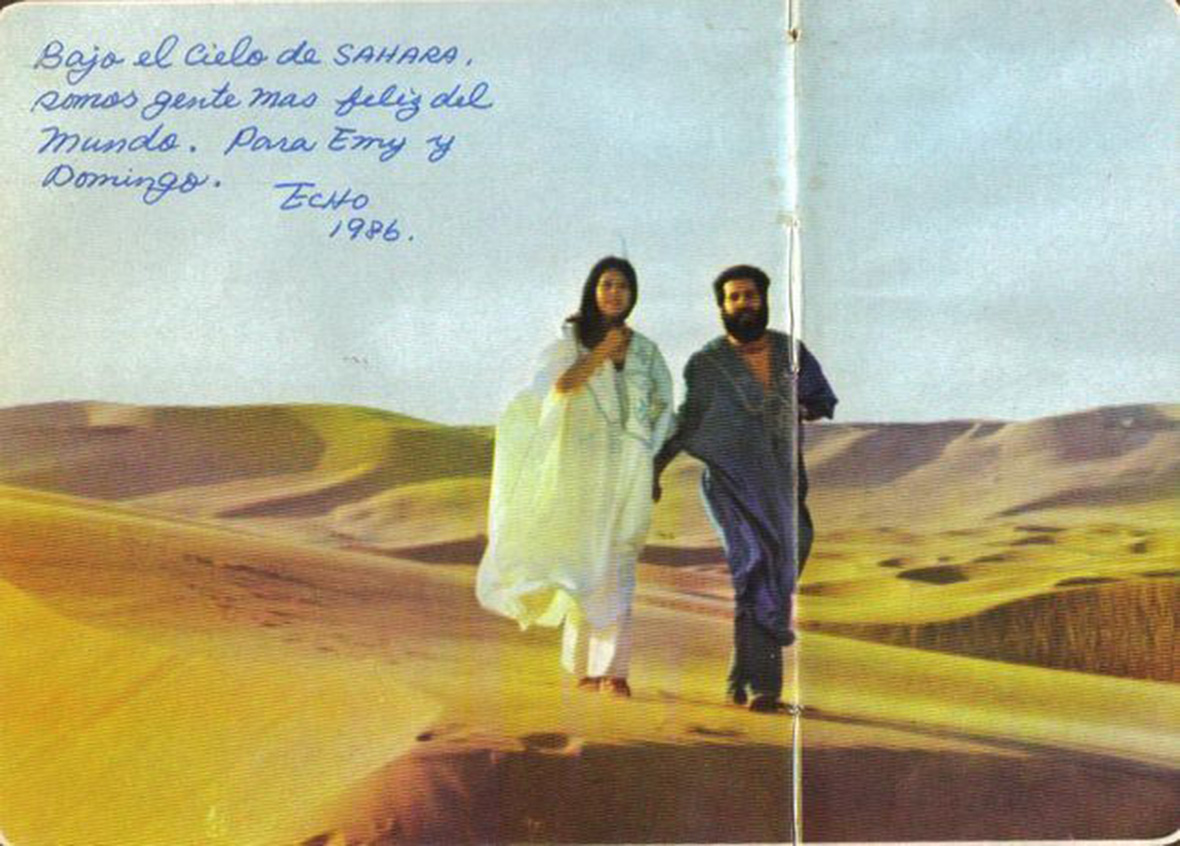

“I don’t remember when it was exactly, but one day I found myself absentmindedly flipping through an issue of National Geographic. It just so happened there was a feature on the Sahara,” Sanmao wrote in the early 1970s, explaining the desert’s pull. “I couldn’t understand the feeling of homesickness I had, inexplicable and yet so decisive, towards that vast and unfamiliar land, as if echoing from a past life . . . My desire to go only deepened, torturing me with nostalgia and longing.” Not content simply to dream, in 1973 she and her future husband José moved from Madrid, where they had been working, to the town of El Aaiún, in what was then the Spanish colony of the Western Sahara.

Sanmao’s account of her life there, Stories of the Sahara, first published in 1976, brought her overnight fame in Taiwan, and it launched her brief but fertile literary career. Over the course of the next fifteen years, she published some twenty books and became wildly popular throughout the Chinese-speaking world. Even today, few writers are as beloved. Now, at long last, the book that made her famous is available in English, in an elegant translation by Mike Fu.

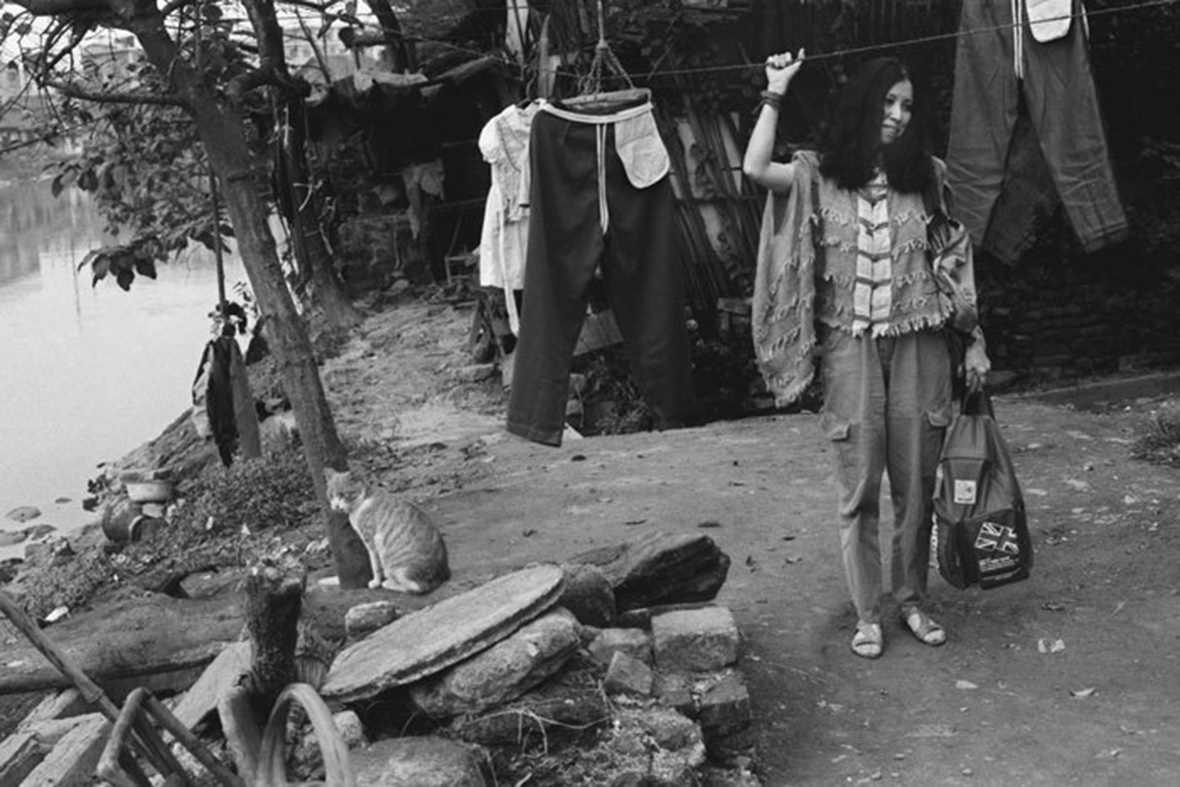

Stories of the Sahara is a series of autobiographical sketches—an intimate, if not always factual, chronicle of Sanmao’s life in El Aaiún with her husband José and their Sahrawi neighbors. The stories offer a glimpse into a world her readers in Taiwan, and eventually in mainland China, could only dream of—a small colonial outpost on the edge of the desert must have seemed unimaginably remote, while her globe-trotting lifestyle must have struck many as a fantasy. “Driving through this great wasteland, so peaceful in the afternoon it was almost frightening, it was hard not to feel some measure of loneliness,” she writes. “But, by the same token, to know that I was wholly alone in this unimaginably vast land was totally liberating.” She traveled the world alone and had little patience for the gender expectations of her day. “Sanmao was unique for her time as an independent Chinese woman,” says Fu. “She not only wrote of her travels far and wide, but expressed herself with a certain boldness and (some might say) vanity.”

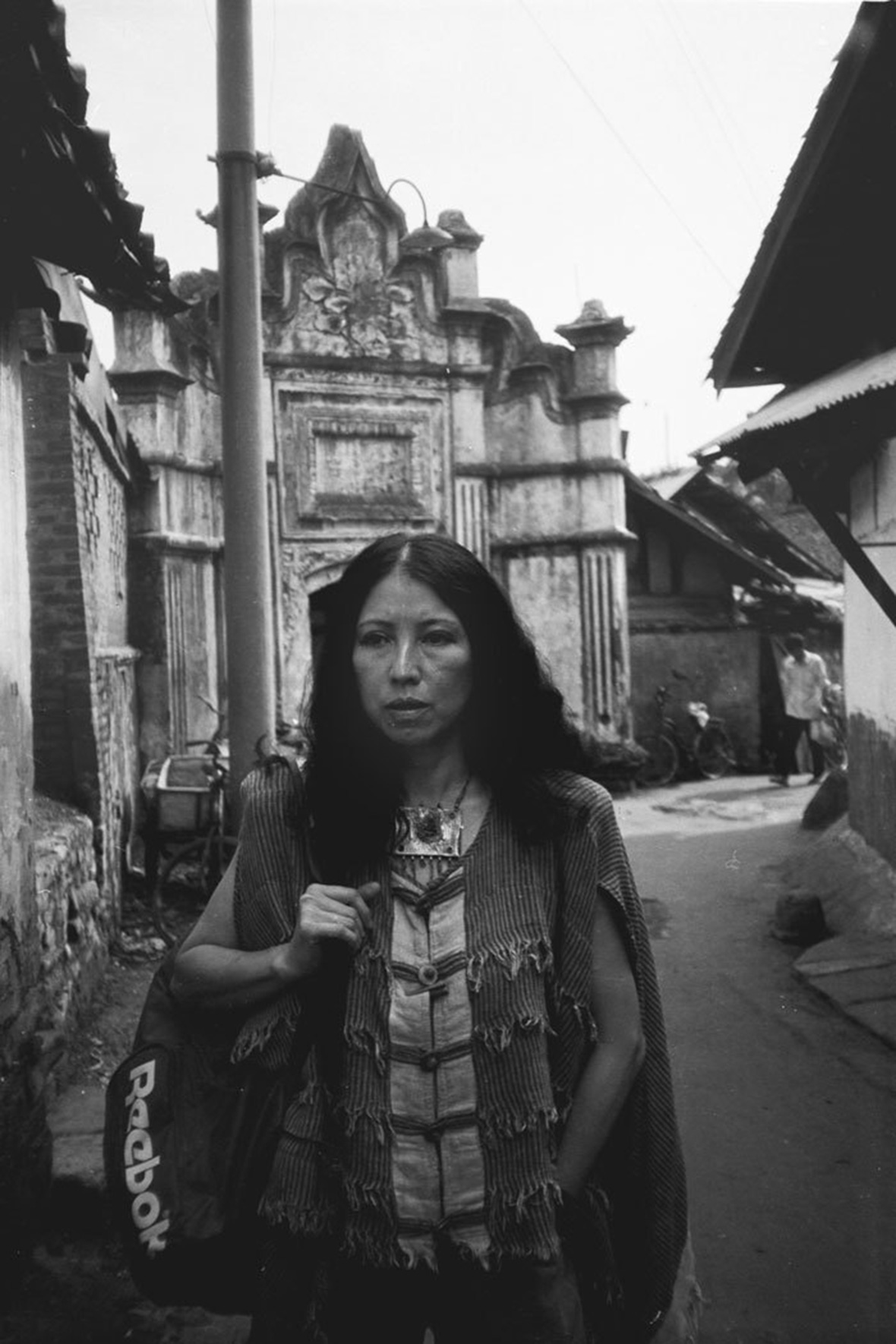

Born in 1943, in wartime Chongqing, Sanmao grew up in Taiwan after her family fled the communist advance. As a child she found her given name, Chen Maoping, too difficult to write, she changed it to Chen Ping; on her first trips abroad, in college, she adopted the English name Echo. Yet it’s as Sanmao—a pen name she borrowed from a 1930s comic-book character—that she became famous. Her literary persona is by turns charming, surprising, and exasperating. “She’s a whimsical character and protagonist, centering the reader as her confidant and co-conspirator,” says Fu. In her hands, even the most outrageous or harrowing situations seem entirely normal. She talks freely of her longing and her disappointments, and though she doesn’t exactly show a vulnerable side, she has no qualms about occasionally appearing ridiculous.

Before moving to the Sahara, Sanmao had already lived in the US, Germany, and Spain. She returned to Taiwan in 1970, but after the untimely death of a fiancé, she left again to take a job teaching English in Madrid. That’s where she began to dream of the desert. José María Quero, a younger man who she had met years earlier, began courting her, and even found a mining job in order to move to the desert with her. She realized that in him she’d found someone to take seriously, and the two got married in El Aaiún in 1974, in a civil ceremony Sanmao recounts in the book. (As a wedding present, he gave her a camel skull. “I was overjoyed,” she writes. “This was just the thing to capture my heart.”) They remained in El Aaiún until late 1975, moving to the Canary Islands when Spain withdrew from the Western Sahara.

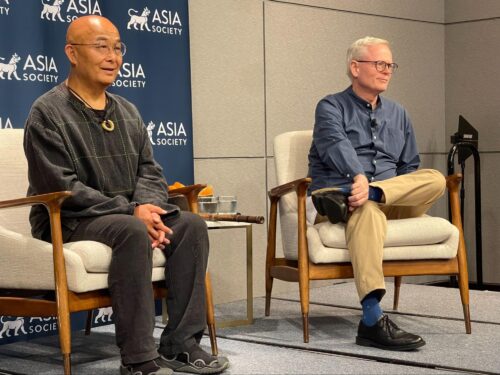

Just why such a singular writer remained unknown in the West for so long is a mystery. “I encountered Sanmao in 2011, when a friend gave me Stories of the Sahara as a birthday present,” says Fu. He had begun dabbling in translation a few years earlier, while doing a master’s in Chinese Film at Columbia, and when he read her he immediately knew he wanted to bring her into English. “One of the first things that drew me to this book was Sanmao’s eminent readability, even for a Chinese-American like myself who grew up largely without deep knowledge of or access to Chinese literature,” he says. “I wanted her to sound just as lively, funny, and relatable in English. I felt that the spirit of her words has aged well and really lent itself to the task.” His version admirably captures her casual, conversational voice, and her personality comes through on every page. (Fu is also the translation editor of the Shanghai Literary Review.)

In recent years, Sanmao has finally begun to attract more international attention, thanks to Fu and other translators. Stories of the Sahara appeared in Catalan and Spanish in 2016 and in Dutch in 2019. Recently the New York Times devoted an “Overlooked” feature (a sort of belated obituary) to Sanmao, and the New Yorker published an essay on her life and works. The upcoming second issue of the Latin American literary journal Chopsuey will include the first-ever Spanish translation of her travelogue from Argentina. And in March of this year, for what would have been her 77th birthday, Words Without Borders published a reminiscence of her by her niece, along with videos of Fu and other translators reading her work in different languages.

What explains Sanmao’s lasting appeal? Partly it’s her curiosity about everyone around her, which in turn owes a lot to her boundless confidence and willingness to flout gender norms. She was a keen observer of the life of El Aaiún and effortlessly moved across social and political lines, meeting Sahrawi notables and colonial bureaucrats, Spanish soldiers and rebel militiamen, conservative women and traveling prostitutes. She and José were much more involved in the local life than their Spanish peers. “We had many Sahrawi friends,” she writes. “The stamp seller at the post office, the security guard at the courthouse, the company driver, the store assistant, the beggar pretending to be blind, the donkey wrangler who delivered water, the powerful tribal chief, the penniless slave, male and female neighbors young and old, policemen, thieves; people from all walks of life were our sahabi.” Not everyone got along, of course, and intolerance and violence were never far from the scene. One of her most dramatic pieces, “Crying Camels,” shows how a mixture of religious intolerance, sexual conservatism, political infighting, and personal vendettas culminated, in the chaotic days of Spain’s withdrawal, in a brutal tragedy.

Her curiosity didn’t preclude criticism, and she never hesitated to pass judgment on what she saw. She deplored the Sahrawi practices of slavery and child marriage, and she was incredulous about local ignorance and poor hygiene. As Fu notes, “there are quite a few instances where her judgments of others, especially the Sahrawi characters, may come off as insensitive at best, derogatory or racist at worst.” Yet her judgments were balanced by a profound sympathy for nearly everyone she encountered: the young shopkeeper duped into sending money to a distant woman he thinks is his wife, the Spanish soldier filled with hatred after his comrades are massacred, the old women who asked her to treat their aches and pains. She found herself compelled by the very landscape to seek out these human connections. “Back in civilization, life was too complicated. I wouldn’t have thought other people or things had anything to do with me,” she writes. “But in this barren land, fierce winds howling year round, my spirit was moved by the mere sight of a blade of grass or a drop of morning dew . . . How could I turn a blind eye to an old man tottering on his own beneath such a lonely sky?”

In 1979, José died in a tragic diving accident on the Canary Islands, leaving Sanmao distraught. She returned to Taiwan, where she settled down to teach writing. Yet before long she was on the road again, spending several months in Latin America on assignment from United Daily News, the paper that had printed her first dispatches from Africa. Toward the end of the 1980s she traveled to mainland China for the first time. By the time of her sudden death in 1991, in an apparent suicide in a Taipei hospital, she had already become a literary legend on both sides of the straits.

Her evocations of life in the Sahara remain haunting. “What attracts me to this place? The wide openness of the earth and sky, the hot sun, the windstorms. There’s joy in such a lonely life, there’s sorrow.” Sanmao’s life and works continue to be an invitation for readers to take a leap into the unknown. And now this singular, alluring writer is available to readers in English.

To purchase Mike Fu’s translation of Stories of the Sahara, click here. The original Chinese version can be ordered here.

Like this story? Follow neocha on Facebook and Instagram.

Contributor: Allen Young

Chinese Translation: Olivia Li

Images Courtesy of Xiao Quan & Chengdu University of Science and Technology