One-Way Street gathers independent voices from China and beyond

Four times a year, a compact paperback with a simple cover hits Chinese bookstores, its pages filled with essays, notes, interviews, long-form nonfiction, book reviews, poetry and short stories by some of the most spirited voices from China and abroad.

This article was originally published on Neocha and is republished with permission.

Four times a year, a compact paperback with a simple cover hits Chinese bookstores, its pages filled with essays, notes, interviews, long-form nonfiction, book reviews, poetry and short stories by some of the most spirited voices from China and abroad. One-Way Street Magazine, as the quarterly is known in English—the Chinese name Dandu name might be translated as “independent reading” or “reading alone”—is a journal that thinks books and ideas are worth arguing about, and for the past ten years it’s created a small but vital space for intellectual debate. Highbrow but unpretentious, it’s a platform for opinions, articles of faith, and moments of doubt—in short, a public conversation about cultural life.

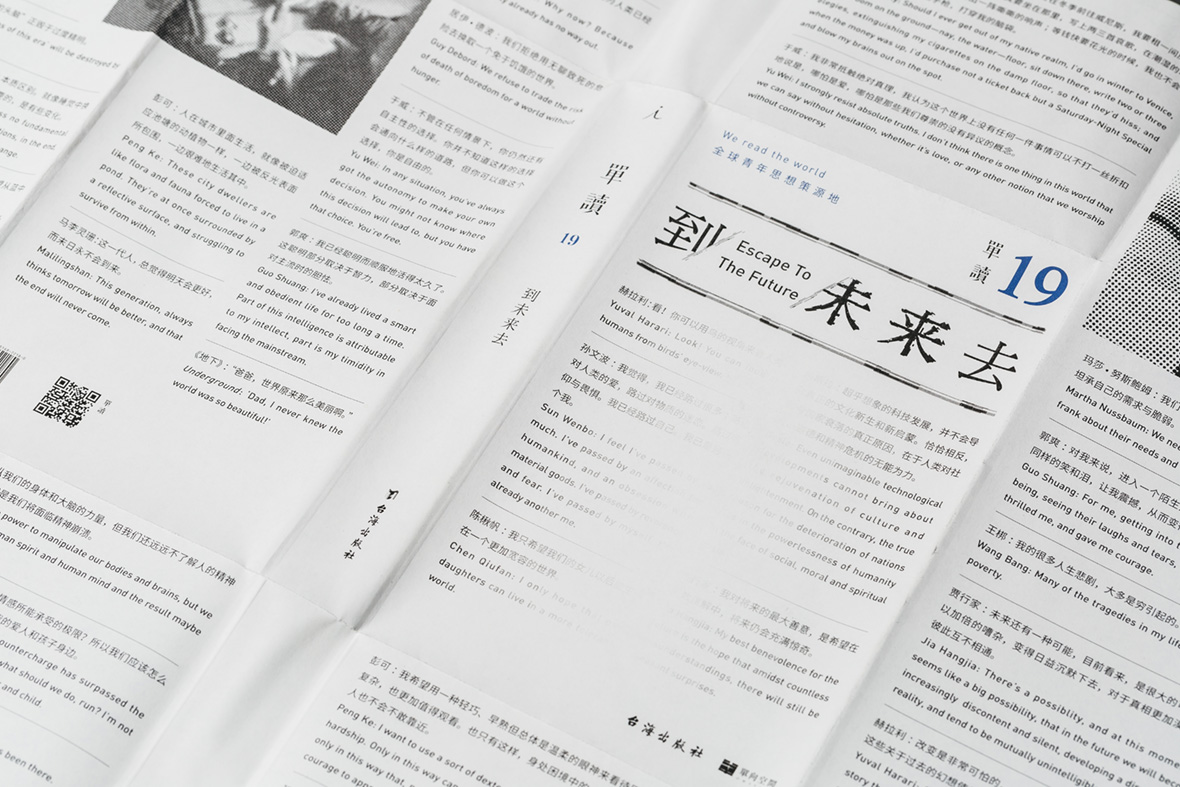

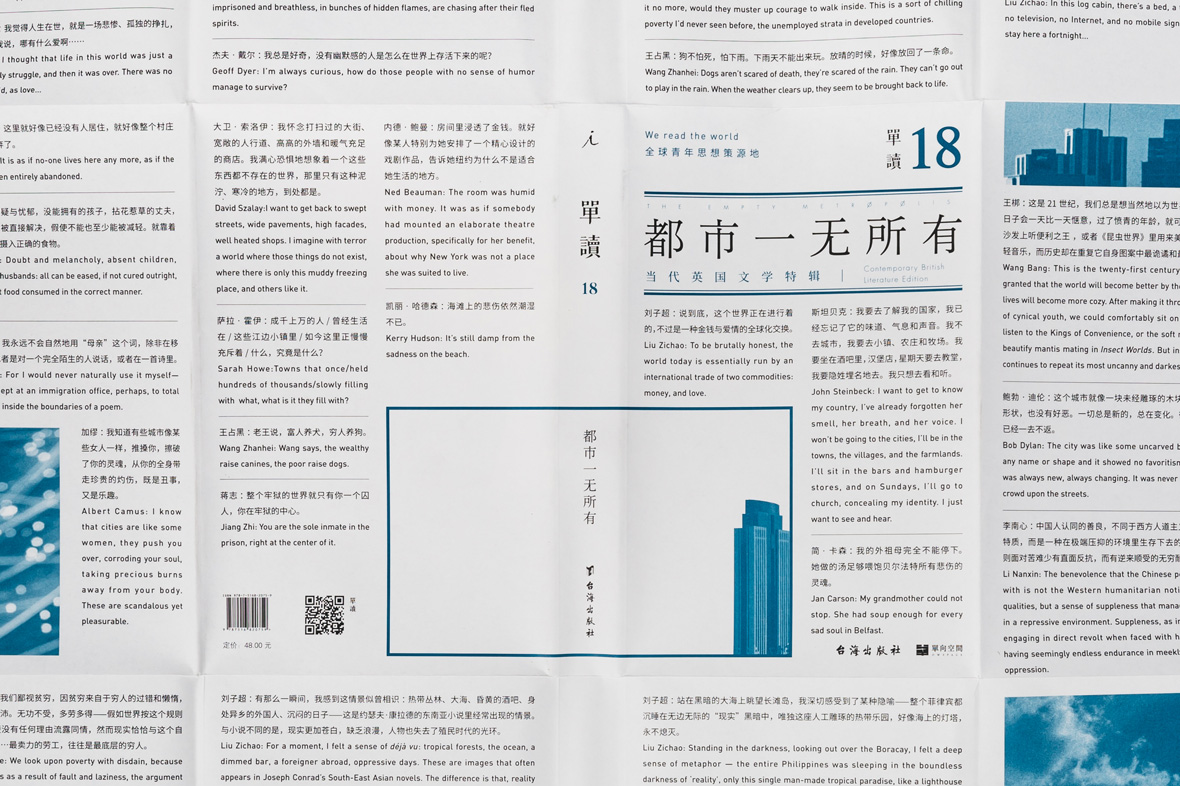

Printed on the cover of every issue is the journal’s English motto, “We read the world,” while underneath a line in Chinese adds: “A source for worldwide youth thought.” One-Way Street aims to put writers from around the globe in dialogue with their Chinese counterparts. “We’re a journal that grew out of a bookstore, and reading has always been our primary vehicle for knowledge,” says Wú Qí 吴琦, the editor-in-chief. “And in a globalized age, we want the object of that knowledge to be the entire world.” Each issue ends with a handful of capsule reviews of new and noteworthy titles that haven’t yet appeared in Chinese. Recently they’ve covered books by Martha Nussbaum, Rachel Cusk, Timothy Snyder, and Teju Cole, among many others, and though there’s a distinct Anglophone bias, this section epitomizes the journal’s mission: to read deep and wide and to respond in a reflective, critical spirit.

Before it was a journal, One-Way Street was a bookstore. In 2005, a group of journalists living in Beijing opened “Danxiangjie Tushuguan,” or One-Way Street Library, named after Walter Benjamin’s idiosyncratic collection of observations on early-twentieth-century life. The shop began hosting lectures and panel discussions, and it quickly made a name for itself as a meeting place for Chinese intellectuals. Four years later, in 2009, when the founders launched a publication—initially also called Danxiangjie—their events gave them a ready list of contributors.

“The bookstore made a point of inviting prominent people from every field to talk about cultural and social issues,” says Wu. “We wanted to create a space that was truly shared, and we very organically gathered people from the worlds of social thought and literature. They became the journal’s first contributors, and many of them, like Yán Gēlíng 严歌苓, Liú Yú 刘瑜, Zhāng Chéngzhì 张承志, Lǐ Yínhé 李银河, and Xiàng Biāo 项飙, went on to have a big impact on contemporary Chinese thought. From the very start, the journal was an attempt to create that shared space on paper.”

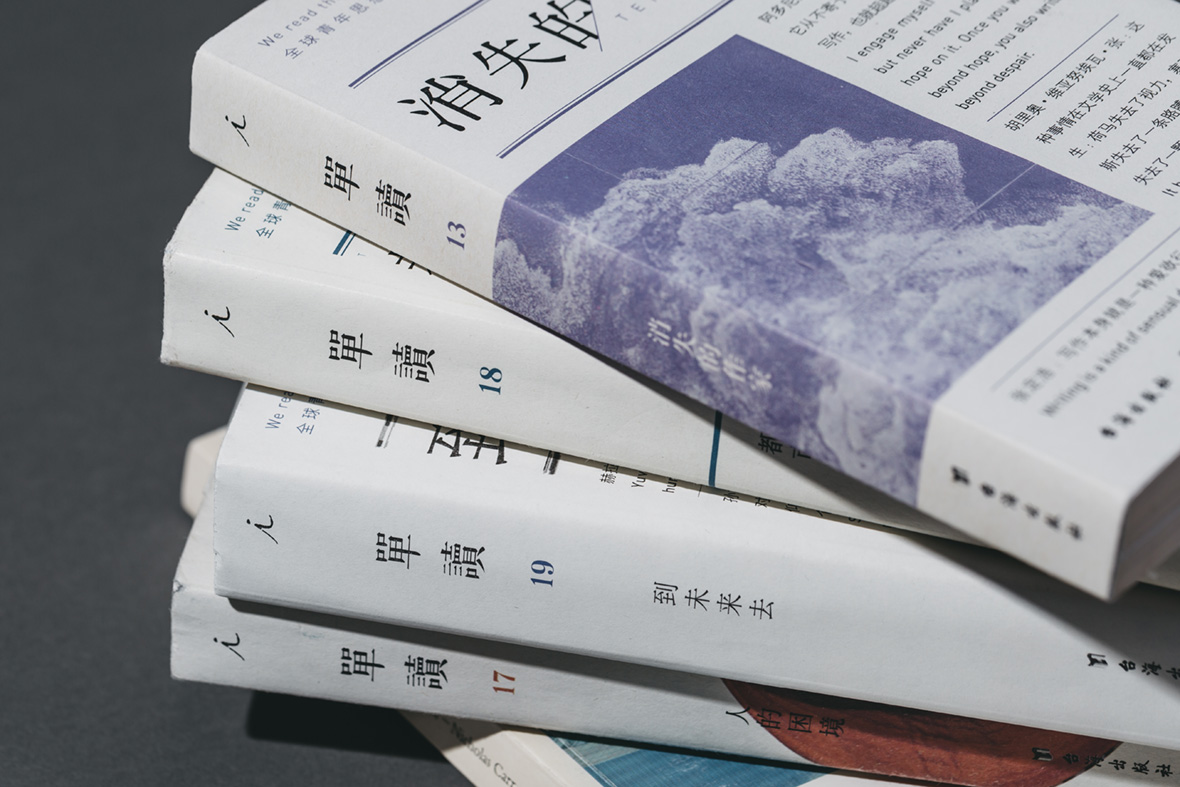

After five issues released more or less once a year, in 2014 the journal began publishing on a quarterly basis and changed its name to Dandu, while the bookstore expanded to other locations in Beijing and changed its name to Danxiang Kongjian, or One-Way Space. Newer issues feature pull-quotes on the cover in both Chinese and English—a nod to the editors’ aspiration to engage the outside world beyond China’s borders. In fact, they now include a table of contents in English along with a short summary of each piece. “We want to introduce Chinese writers abroad, as well as to bring foreign writers in, and language is a barrier,” says Wu. “Hopefully one day we can publish a special issue in English.” To that end, the journal has begun collaborating with the Los Angeles Review of Books China Channel and Paper Republic to make some articles available in translation. Neocha is likewise pleased to include an exclusive English edition of Wu’s recent essay “Arriving in London” below.

“We want each issue’s theme to address current topics of discussion in contemporary Chinese society, and at the same time to have a deeper theoretical or intellectual background,” explains Wu. “Escape to the Future,” an issue published in 2019 (no. 19), includes an interview with Yuval Noah Harari, along with essays by 贾行家 on the future of language and Yú Wēi 于威 on personal autonomy. Not every article or story takes up the topic; the themes don’t draw a border so much as give each issue a center of gravity. Others include “The Empty Metropolis (no. 18, special issue on British literature), “The Age of Anxiety” (no. 9), and “Is the Avant-Garde Dead?” (no. 2). They try to strike a difficult balance—timely but not ephemeral.

One-Way Street has a website, an app, podcasts, and WeChat and Weibo accounts, yet its heart is in print. In fact, the editors seem to regard the online world with a certain suspicion. “We’re children of Gutenberg,” wrote Xǔ Zhīyuǎn 许知远, one of the journal’s founders, and still its most widely known figure, in the introduction to the inaugural issue, back in 2009. “What we fell in love with was the stillness of reading alone under faint light, the logic that strings one sentence to another, the surprises between the lines. And staring at a computer screen, constantly interrupted by an MSN chat window, with messages coming one at a time, is hard to take.” This dedication to print is less an eccentric or nostalgic whim than an attempt to resist the distraction of online media. To read their stories, you can’t always go online—you have to get your hands on a paper copy, or at least an ebook. In an age when every smartphone is refreshed with trivial, mindlessly scrollable “content,” One-Way Street insists on a format that requires patience and attention.

With its slightly contrarian posture, the journal is what in China is called xiaozhong: it appeals to the “small crowd” because it deliberately goes against the mainstream. Its critical spirit offers an alternative both to the reigning consumerism and to the bland official values touted on posters across the country. It’s an insistent, bracing reminder that the world doesn’t have to be the way it is.

Yet in recent years the space for such independent voices in the public sphere has begun to shrink rapidly. “I never thought the changes would come so quickly and abruptly,” Wu admits, describing the shifting media environment. “Not just in the past 10 years, in the past five years, the atmosphere for publishing and for cultural critique has drastically changed. In general the space for speech has contracted, while materialism is on the rise.” Hemmed in by censorship and corroded by distraction, the public sphere itself is unrecognizably changed. This gives the early issues a certain poignance—and makes them seem unsettlingly prescient.

Looking back now, essays from those early years read like dispatches from a bygone world. In a piece from 2010 titled “A Slip of the Tongue,” which opens the second issue, Xu Zhiyuan laments how the advent of the digital age seems to have left intellectuals in China in a daze:

Over the past ten years, people have witnessed a technical revolution sweeping across the whole of society, bringing unprecedented public involvement and reshaping the social mood. Yet intellectuals have lost the ability to respond—there’s not so much as a single impassioned debate. A more powerful system has taken shape, and even though it seems free-wheeling and rowdy, firm control and anarchy can exist side by side. Most of the time people are happy in the system, and they can no longer clearly tell whether it benefits, implicates, or harms them, or all three at once.

How can I put these vague impressions into clearer words? A heavy shower has just fallen, the air is fragrant with grass and earth, and I have no clue where to begin.

It’s a lament and a call to arms: Xu urges intellectuals to make themselves heard on the public stage. And despite his professed impotence, his words here are themselves a beginning, as are his many other essays, along with the whole collective endeavor of the journal. One-Way Street is an attempt to reclaim a space for the intellectual in the Chinese public sphere.

As for Wu, the current editor, he’s far from pessimistic. “If you want to complain about something, that’s easy,” he says. “Yet if you’re really interested in publishing, in the media, in the culture of knowledge, then you just have to keep working no matter what. I see a lot of barren land that needs cultivating, so we have plenty of possibilities. You can’t give up on yourself too soon.”

Click here to read Neocha’s exclusive English translation of Wu Qi’s essay “Arriving in London,” from issue 18 of One-Way Street Magazine. Click here to visit the bookstore’s page on Taobao.

Like this story? Follow neocha on Facebook and Instagram.

Website: owspace.com

WeChat: dandureading

Weibo: ~/onewaystreet

Contributor: Allen Young

Photographer: David Yen

Chinese Translation: Olivia Li & Chen Yuan