Our weekly explainer series, China Ties, looks at China’s relationship with different countries of the world.

A railway says more than 1,000 political slogans. In 2014, the Istanbul-Ankara high-speed line was finally finished, a vast project linking Turkey’s two major cities, passing through Turkey’s most urbanized area on a journey that now took just three and a half hours, compared with the previous plodding 10. The project was jointly funded, largely by the European Investment Bank, but with China Exim Bank coughing up $720 million for the final stage.

That’s Turkey’s foreign policy in a nutshell: Stuck between China and the West, it uses this geopolitical and geographical position to get the best deal. Politicians in the U.S. and EU grind their teeth at Turkey’s support for Russia in the war in Ukraine, while China berated Turkey in 2019 for its military presence in Syria and no doubt stews over its outspoken Uyghur diaspora, the “largest outside of Central Asia,” according to Nikkei Asia. It’s a balancing act that this month’s election — where President Recep Tayyip Erdogan is being challenged by Republican People’s Party (CHP) candidate Kemal Kilicdaroglu — is unlikely to change.

The P.R.C.-Turkey relationship started in 1971, when Turkey severed ties with Taiwan’s Nationalist government and recognized the Beijing-based government, in line with America’s move to friendlier relations with Mao. Back then, Turkey was in step with the U.S. — a member of NATO since 1952, and Washington’s foothold in the Middle East, acting as a buffer against Soviet incursion in the region.

The fall of the USSR led Turkey down its own route in foreign policy. Officially, the country “does not want to lean to one side” in the growing struggle between China, Russia, or the West, says Kadir Temiz, a professor of international relations at Istanbul Medeniyet University.

It gets what it can out of Chinese investment. Ever since the two countries upped their partnership on China’s business-like alliance hierarchy to a Strategic Partnership Cooperation in 2010, China has invested in Turkish infrastructure and telecoms, alongside a 65% stake in a large container port just outside Istanbul and two major coal-fired power plants. Where Western governments have viewed Huawei’s 5G networks with distrust, Turkcell (Turkey’s leading telecom company) sees opportunity, signing several agreements to develop the country’s 5G network.

Geopolitically, Turkey could be China’s opening to the West, notes Jakob Lindgaard, a senior researcher for the Danish Institute of International Studies. Turkey’s NATO membership and strong trade links in Europe “could play in China’s favor” while the world divides into two blocs.

In trade, too. Turkey dreams of being a logistics hub between East and West — the so-called “Middle Corridor” plan — which the BRI can tap into. The country signed an agreement to align the two plans in 2015, but Temiz says there is no evidence China wants Turkey to become a BRI hub anytime soon.

Republic of Türkiye

Founded: October 29, 1923

Population: 85.8 million

Government: Constitutional Democracy

Capital: Ankara

Largest city: Istanbul

Established relations with PRC: August 5, 1971

Turkey’s currency crisis and high inflation meant it leaned further and further into China in 2019 and 2020, triggering concern that Turkey was becoming a “client state.” Chinese banks bailed out the lira when it lost 40% in value in 2018. In 2017, Erdogan (who in 2009 had declared a “genocide” was being waged against Uyghurs in Xinjiang) made an extradition treaty with China that led some to worry Uyghurs in Turkey would be arrested and deported. Turkey was early to buy Chinese vaccines during the pandemic, with Erdogan and other ministers publicly getting a jab.

But China doesn’t get it all its own way. Temiz and Lindgaard note ongoing rifts, including China’s treatment of Uyghurs, and both countries wanting greater influence in Central Asia and the Middle East.

Turkey has become a haven for Uyghurs, forming a diaspora somewhere between 10,000 and 50,000 strong that is not afraid to protest China’s Xinjiang policies. Turkey has remained relatively quiet on the Uyghurs’ plight, but in 2019 brought up the matter of Chinese “torture” in a session of the UN. And this past January, Turkey’s foreign minister revealed, “China is disturbed by our position defending the Uyghur Turks’ rights before the international community.” China has responded by closing consulates and threatening economic consequences.

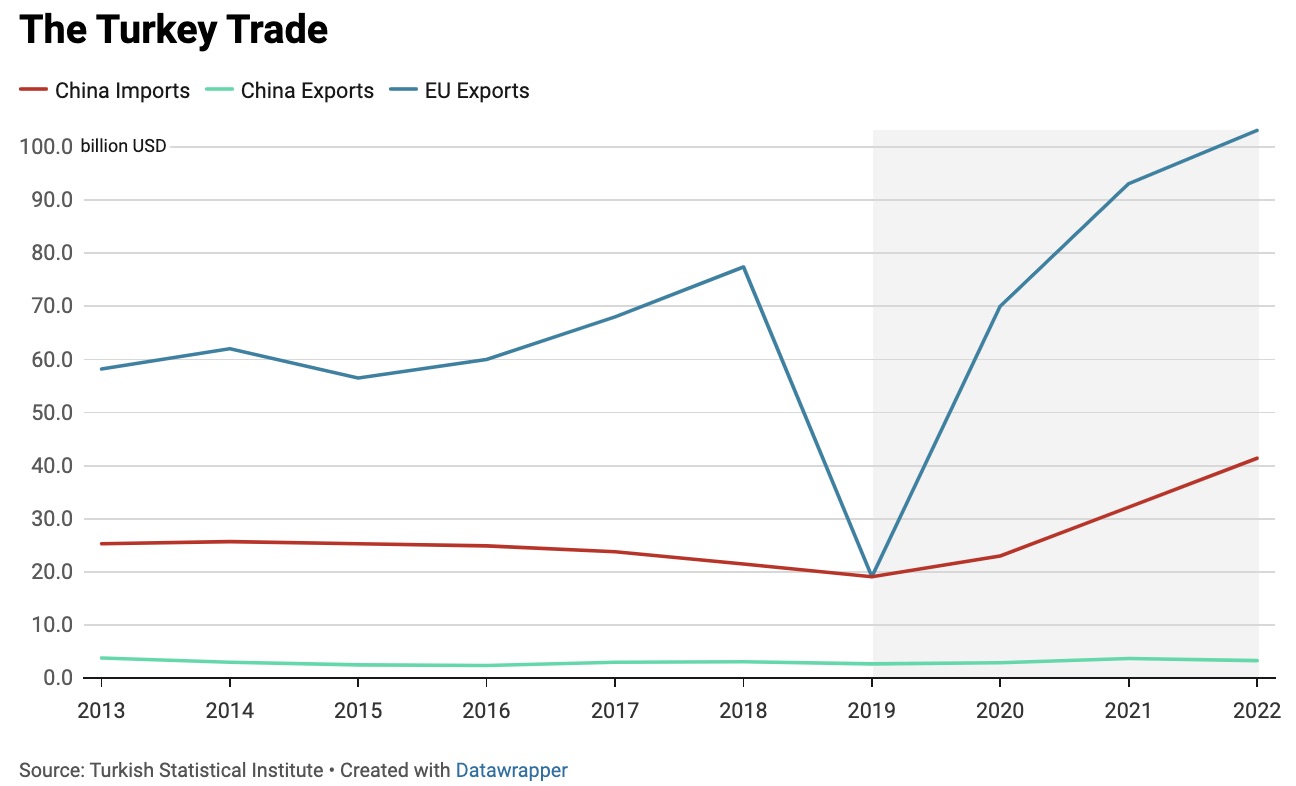

Because Turkey now depends on Chinese trade more than ever. Imports from China doubled from 2019 to 2022 (only Russia sends more), while EU exports have seen a corresponding spike, leading some to argue Turkey is trying to save its economy by buying half-finished goods cheap from China, finishing them domestically, then selling them to the EU.

But that import value pales in comparison with what Turkey gets from its EU exports, and Lindgaard points out that Germany and the Netherlands are “by far” Turkey’s biggest investors — China’s estimated $5 billion looking like small fry in comparison. So for now, Turkey depends on keeping both sides happy.